Copy of A Pair of 1640’s Stays: Part 2

/Last week, I wrote about creating a set of 1640’s stays: about collecting the client’s preferences, selecting and scaling up the pattern, and stitching up the stays ready for fitting. This week I will compare the original scaling to the actual fit of the stays and discuss the effectiveness or otherwise of the Barra system for this use.

Scaling Re-enactment Patterns

Many re-enactors who make their own costume, and those that make costume for others, take their original patterns for garments from historically researched books. These patterns come from various sources - they might be based on an idea of how to get the right outline or shape, a summary of real garments amalgamated into one pattern, or an exact copy of an original garment that has survived in a museum. Very few of the patterns given in books are done so with any real indication of how to adapt the pattern to suit the tall/short, thin/fat, straight/curvy modern wearer.

In my previous post on 17th December, “Book Review with a Twist: Modern Maker 1”, I discussed using the Barra tape method described by Matthew Gnagy that he had interpreted from Spanish 16th and 17th century tailors’ manuals. In the comments following that post, Fran Grimble pointed out that apportioning scales like them were being used in the 18th, 19th and 20th centuries as well (Fran Grimble, www.lavoltapress.com). When creating the paper pattern for the 1640’s stays below, I used a version of the Barra tapes to scale up the pattern from the book scale at the same time as making changes to suit my client’s shape as opposed to the shape of the original wearer. This pattern comes from Patterns of Fashion 5 by Janet Arnold, Jenny Tiramani and Luca Costigliolo.

1640’s stays made with modern materials

Defining the Book Pattern

In my December post, I spoke about using a small barra tape at the scale of the book to identify the key measurement points of the original pattern and their relationship to the original wearer. I could not go back in time and measure the original wearer’s waist, chest or height, so I had to find some other way of identifying their key statistics. In the case of a pair of stays, this is fairly straight forward as the stays are very fitted to the actual body of the wearer with no “ease” - in fact they have negative ease in order to pull in the more squish-able parts of the torso. However, a less fitted item such as a coat would pose more serious problems in identifying the original wearer’s body measurements from the presented garment pattern.

In this case, I felt happy to proceed in the following way. I identified on the book pattern where the wearer’s waist and chest measurements would most likely be measured in each pattern piece. For this pattern there are two pieces, each cut twice, that make the four panels of the stays plus the one piece of the stomacher. Locating the waist on the panel pieces was easy - the back panel actually comes into a narrow place and the front panel has a set of gores that lie along the waist line. Using the point at which the waist line passed out of the front edge of the front panel indicated where on the stomacher the waist was located. Adding all of those measurements up would be slightly too large, since the stomacher overlaps the front panel somewhat, so I reduced the summed value by an arbitrary amount that I guessed, based on the photo of the surviving original stays, to account for that overlap. That last bit was less than scientific but the best I could come up with at the time!

Identifying the chest location on the book pattern was harder. I went for a curve passing under the bottom of the arm hole curve and through a location on the join of front and back panels, below the highest point, and then across the stomacher at a related height. Please remember this fuzzy description when it comes to the fitting below!

I now needed a height measurement. I decided that trying to both guess and then use the actual height of the person was not relevant. As a person with short legs in comparison to my back length myself, I neither wanted to extrapolate from such a short garment nor then apply that to my client! A much more relevant measurement for stays is the nape of the neck to the natural waist. This length is based on the bone structure of the spine, not the length of their legs, it is not affected by posture too much and is related to other bone lengths in the same area, such a shoulder width. So, I measured on the book pattern from the waist that I had identified above to the top of the back panel and then I added a small additional amount to account for the gap between the top of the stays and the nape of the neck. Since these stays come up high on the shoulder, this was not too prone to error; had they been scooped low in the back this would have been prone to far more error in the proportions and I would have adjusted it in line with a shoulder strap or other indicative measure.

All that measuring gave me an original wearer with a compressed bust and waist of 32” and 25” and a nape to neck of 13”. Despite being British, and using all metric measurements at work, I am afraid I still think in inches when dressmaking!! Since these measurements looked reasonable to me as a possible real woman and they seemed to fit the photo of the displayed original stays, I moved on to constructing the pattern.

Stays with binding strip of gross-grain ribbon

Scaling Up the Pattern

At this point I made up three “barra” tapes. Not at 32”, 25” and 13” but at 6.25”, 8” and 3.25”. These reflect the book scale waist, bust and nape to neck - i.e I could use these tapes to measure round the waist or bust of a woman if she were the same scale as the book, in this case 1/4 of her real size. These small tapes were used to measure off the key pattern points, exactly like shown in Matthew’s book using the half mark (M), the quarter mark (Q), the third mark (t) and so on. I started by identifying one of the squared paper lines in the book to be the vertical starting line and one to be the horizontal starting line. From there I measured DOWN the pattern from the horizontal to locate the height of the waist gores, the depth of the arm hole curve, and so on. Then I measured OUT from the vertical line to identify the width at those places and also the front panel, the side seam, etc. The key points of the pattern are changes of direction, widest points of curves, key features such as gores or shoulder straps, and so on.

Then there was one more complication to deal with. The stays that my client wanted do not have a stomacher, instead they meet in the centre front. I did not want to go for ones that fully meet as there is no room for adjustment over time, but I did need to add more width to the front panels to make them more fully closing and I would put a modesty panel behind the lacing. I made these adjustments by dividing in 2 the width from the stomacher that I had allowed in the waist and bust measurements above and adding those values to each front panel in front of the shoulder strap upright, thus making the front section of the front panel wider.

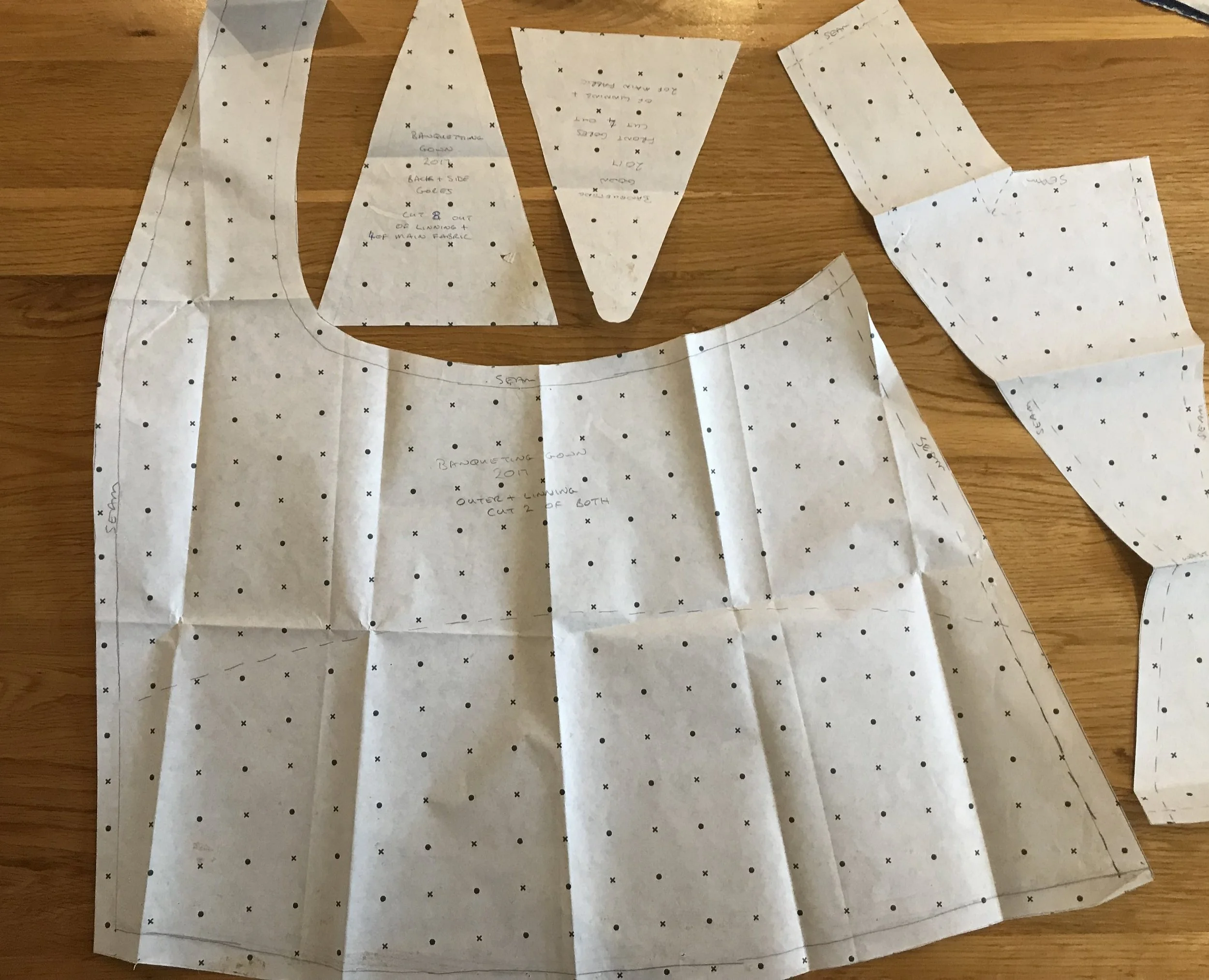

My first attempt looked like this. It is wrong so please do not copy and use it but I was able to correct some of the errors by “the look of it” on the full scale paper pattern and before progressing to cutting fabric. However, it shows the use of the barra portions and the use of the length tape (L), the bust tape (C) and the waist tape (W). Measurements written on the vertical line have been measured DOWN from an unseen horizontal line using the C or L tapes. Measurements on the pattern are measured OUT from the vertical line using the C or W tapes.

How did I decide which tape to use? Well, I guessed, but from the starting point of looking at the drawings that Matthew Gnagy interpreted from the tailors’ manuals. On the whole, they use L or C for lengths and C or W for widths. The bust tape (C) used for lengths allows more fabric ease to make movement easier. Other than that I think it makes sense - bust for measurements around the arm, chest and upper back, waist tape used for the lower back and hips.

First attempt at stays pattern using the Barra method

How does this save time or make things better? The first time it does not! In fact this took far longer to do than I could put in the price of the garment. However, the next person to buy this design from me will not need any maths or arithmetic to be done. I will simply start with a sheet of pattern paper, draw the vertical line, select the correct L, C and W tapes and draw the pattern. I could draw it straight on the fabric but I do not trust my own drawing skills that much!

Did it work though?

Yes! Far better than I actually anticipated. I had left extra room in the seams and length in the body to allow not only for errors in the method but also for differences in the client’s shape. The fit at the waist and hips was perfect as it was sewn. The front panel was slightly too long both at the bottom (about 1”) and the top (about 0.5”). However, the length in the back panel was perfect. The waist line sat on the client’s waist and the shoulder straps come round her shoulder like the original stays.

The place it did not fit quite so well was the bust, I had made two errors. First, I had underestimated how well endowed my client is (a nice complement to be paid I think) and also, I had not created sufficient room under the arm. Anyone who can interpret the sketch above will spot that one of the original errors on the sketch as too short a distance from front to back of the armhole and my fix for that problem was not sufficiently bold. Taken together, these things meant that the front of the stays gaped open too far and the front shoulder strap was too close to the arm. The extra seam allowance that I left in the back seams, shown in the photo below, is more than sufficient to make up for these errors and should provide an excellent fit once adjusted.

One thing that I was pleasantly surprised by was the shape of the back panel. The effect of the carefully drawn curves and tricky-to-sew side seam is that the tall back panel curves over the shoulder blades in a pleasing way, preventing that odd effect of boned fabric sticking up and out at the shoulders. A nice discovery about the pattern making skill of our forebears that I was not expecting.

Back of the stays partially completed prior to the fitting

The last thing that I need to do before completing this project and posting it to client, is to adjust my sketch pattern to have a wider area under the arms and reduce the front length slightly. That way, the next one that I make should fit better at the first fitting.

Should you like to order a set of made-to-measure 1640’s stays - or any other English Civil War women’s costume - please see the other pages on this website or contact me using contact form or the Facebook link at the bottom of the page.