It costs how much???

/As I described in my last post, last year I decided to branch out in my life and start a part time business making re-enactment costume for sale. I had been making costume for my family for nearly 30 years and was considered by family and friends to be good at it but how would I go about doing it for strangers and charging them for it?

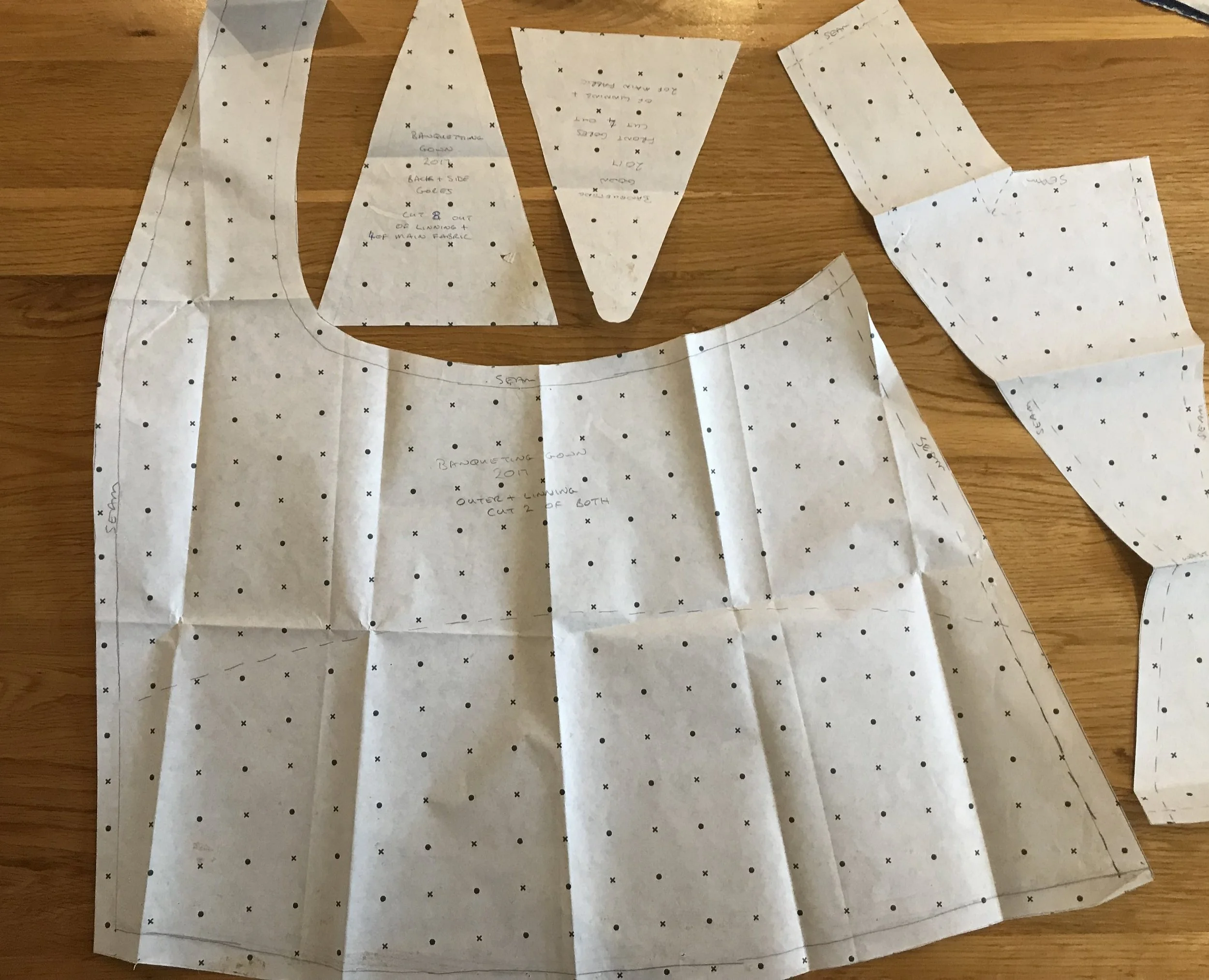

Although a lot of re-enactment costume is custom made and therefore impossible to price in advance, I am fortunate to be involved in The Sealed Knot where the word “uniform” is not a dirty one. There are some basics bits of kit that all participants need - depending on their chosen display gender and role (soldier, female civilian or male civilian). One of my first tasks then was to generate some costs to produce these basic items so that selling prices could be estimated and published, giving customers a feel for the cost of my clothes and an indication of costs for more elaborate or personal items.

Doing this made me think about why re-enactment clothing is so expensive compared to the high street clothes we buy every day at much lower prices. This blog leads you through the thought processes I used while determining what my products would costs and comparing them to buying modern clothes on the High Street. As an example I will use a fictional Soldier’s Coat on offer at £150.

Choosing an Authenticity Level

The major cost in producing clothing in the UK is labour. It was not always this way. In 1645, George Wood wrote of spending 17 shillings apiece for several thousand suits of clothes for the standing army each comprising cassock (a kind of coat) and breeches (knee length trousers). He listed it out like this,

16 shillings for the fabric for both,

3 pennies for a leather pocket for the breeches,

1 1/2 pennies for the tapes and strings,

1 penny for the buttons and hooks

just 10 pennies for a tailor to make up each suit.

The proportions are very different now, with the cost of making up clothes more than half of the value of the clothing. With labour such a large part of the cost, the nature of the fabrication becomes very important. If you use modern standards of production - standard “off the peg” sizes, machine sewn hems, buttonholes and visible machine stitching - then the labour cost is reduced but the market for your clothes is restricted to the “newbie” recruits who have not yet decided to invest heavily in their hobby.

If you go for full historical accuracy only - all seams and stitching done by hand, hand sewn button and lacing holes, fitted to the individual at pattern drawing and final assembly stages (that means you or your client have to travel to be in the same place on two occasions!) and so on - then the number of hours of work is much higher so the labour cost is very high for each item of clothing. Only the true enthusiasts, will pay for this kind of construction on every item that they wear. For example, someone who regularly demonstrates their hand made clothing as part of a living history display. Most people like this make their own clothes like, um, me!

Most re-enactors go for products between these two extremes - they invest where it shows so are happy with machine sewn hidden seams and machine buttonholes for clothing underneath but look for more authentic appearing construction on the outsides. They want to be able to select this to suit their personal budget. Several people in my regiment, Prince Maurice’s Regiment of Dragoones, said they would prefer to be able to choose some of the levels of finish, so I embedded that choice in my philosophy.

There were two things that I knew. Firstly, I wanted to make clothing from historically accurate patterns. Secondly, I wanted to make clothes that fit the customer better than standard pre-manufactured sizes. Both of these immediately took me out of the basic newbie category and they are also the first reason why costume is so much more expensive than High Street fashion.

Finally I decided on offering a range of basic articles with three or four levels of finish from almost all machine stitched through to almost all hand stitched but in patterns derived from original garments and where I create a new pattern specific to each customer’s measurements so that it fits that person well. Now I was ready to start some calculations.

Hand stitched buttonholes

And Also

The cost of the materials and my time are not the only factors, however. Having been involved in (but not responsible for) project estimating for construction projects, I was aware of some of the other things that need to be included, such as:

Non-productive time - time spent doing accounts, writing adverts and placing them, shopping for fabrics, communicating with customers and potential customers. I worked this out based on a full time business as 1.5 days per 5 day week - that’s a lot of time not spent sewing and needs to be allowed for. When working part time (in my case 1 day per week initially) this value does come down a bit but not to the level that is sustainable at that scale, so I decided that some of this would have to happen in my own “spare time” for a while.

Business costs - insurance, website hosting fee, standing bank charges, regular maintenance of the sewing machine and so on. These mount up quickly if not allowed for a little on each product sold.

Premises - in my case I set this to zero as I work from home but actually I should have allowed something to recover the cost of converting one bedroom into a work room. We rationalised this away because my husband and I had decided on the work room for personal enjoyment before the business was even a concept.

Trading fairs - I had previously decided that I would not be “trading” in the sense of standing behind a table at every possible event trying to sell ready made items. However, my husband and I agreed that two or three trading fairs each year, such as The Original Re-enactors’ Market, would be an excellent investment. So the cost of travelling from Edinburgh to somewhere like Coventry, paying the market fee and accommodation was included for three possible events.

Now I had my overhead costs. To get this in a form that I could use per product I might make, I needed to relate it to a working hour - an hour spent sizing and cutting patterns, cutting cloth, sewing, doing buttons or ties, hand finishing the bits that show. I worked out the total of all the costs above that would be incurred in a full year. Then I worked out the number of working hours per year. This was done the same way that I have seen done by accountants at work - 5 weeks of holiday (unpaid because I am a mean employer!), 1.5 weeks bank (statutory) holidays, 0.5 weeks sick leave and 1 week of training = 44 working weeks per year. I will work 8 hours per week, so there will be 352 working hours per year.

By dividing the total yearly cost of the items in the list above by 352, I had the overhead cost per working hour to use when working out the product cost below. For the example Soldier’s Coat, let us say that this has worked out at £2 per working hour.

The easy bit

In the 21st century, the cost of fabric, linings, trim, buttons, etc is different than it was in the 16th century, however, the same principal applies. For each product it is fairly straightforward to write a list of the materials needed to manufacture that item. For example, let us say the Soldier’s Coat needed

2m of wool fabric,

2m of wool or linen lining

1.5 m of canvas or interlining

A number of buttons

Some sewing thread

For estimating in advance before any orders are received there is some estimation involved here. A short, slim person will need less fabric than a tall, stout person. One coat may need 11 buttons, while another need 20 buttons to make the style look right. Also, the cost of the fabric, buttons, etc is not fixed so I had to look around for “best value” fabric while trying not to be trapped into only being able to use one colour from one supplier as it was the very cheapest. There is a risk element that I will not be able to get fabric at that price when I need it! For re-enactment purposes, especially any activity involving gun powder or fires, only pure wool and pure linen can be used as pure wool has a fire suppressing nature that cotton or modern materials do not.

Let us say that the cost for the Soldier’s Coat was calculated at £70. These specialist materials are the second reason that costume is more expensive that High Street fashion.

So for my pricing estimates there was a lot of judgement and internet searching involved in determining the right costs to allocate to a “standard coat” or a “standard bodice”. Whether my judgement was right and the research was sufficient, only time and selling products will tell. For each item I make, I currently assess what did that item really cost compared to the “standard” version - one of the non-productive tasks mentioned above. In one case, this task revealed an error in the original pricing of a garment I was about to post so I was able to give a small rebate on the final cost. Whether I will continue this garment-by-garment review or not I can’t say but the two values are proving to be very close to each other so far, except that I initially forgot to add the cost of having fabric and other things posted to me!

Linen being cut as a lining for breeches

“It Took Me Ages”

The last element of the cost to produce a single item is my time. I decided that now I am in the “rag trade” instead of engineering, and being a bit Victorian in my management philosophy now I am the boss, I should give myself a healthy pay cut! To this I needed to add (should I ever have enough turnover to pay it) employers liabilities such as NI. I decided against a company pension plan on the basis that I get one for the other 4 days per week and the only shareholder might run off with the cash! More seriously, if this business works, then it will boost my current pension for as long as I am able to do it.

Having read up about sole trader “employer’s” liability I found out that it is pretty minimal and as long as I don’t actually pay myself a wage out of the bank account, then income tax is based on whatever is left after I have paid all the bills, whether that is £90 per hour or 9 pence per hour. So the pay cut mentioned above is just a notional number to allow me to estimate the “value” of my time in a product.

For each type of product, I listed out the key tasks and tried to estimate a time required for each. A fictional list for the example Soldier’s Coat is given below.

Making a made-to-measure pattern from a standard one = 1 hour

Cutting out the parts = 0.5 hours

Sewing the main body = 1 hour

Sewing the sleeves = 1 hour

Hand sewing the lining to the outer = 2 hours

Machine buttonholes and buttons = 1.5 hours

Total of 7 working hours to produce the garment.

Notice the reference to working hours as described in the section above. To get the cost of the 7 working hours, I added the hourly “pay” plus the overhead cost per hour from the “And Also” section above. And that is the third reason that costume costs more than High Street fashion, which is often produced in areas of the world with low pay rates and using techniques or machines that speed up production - no hand stitching in the average GAP or Mark and Spencer blouse.

Using a hand cranked sewing machine for adding a chamois leather pocket

And Finally

After bringing together the overhead costs, the materials costs and the labour costs, this method makes the items look very expensive so I had to keep checking back on my market and competition research that I had been doing for the business plan. I had identified that there are three ranges of re-enactment or historical costume prices out there. There is the “I am just starting out and can’t afford much but don’t care as long as it looks OK” range - completely and obviously machine sewn, often produced abroad and very mass-produced looking. Then there is the “ over the top, modern fashion fabric, full outfit at once, amazing fancy dress” range that costs over £1,000. In the same price range are the designers and suppliers of costume for lead actor/actress stage costume, making clothes that need to stand up to the rigours of stage life and still look opulent.

Finally there is the mid-range suppliers of carefully made, often made-to-measure, single items from craftsmen and craftswomen. These people are aiming for hobby re-enactors or possibly museum displays. When I calculated my costs I was in the top end of this group. Time to sharpen the pencil as our salesmen at work say.

In our example of a coat on sale for £150, if it requires £70 of fabric/materials then there is £80 left to pay the tailor. At 7 hours of production that is £11.43 per working hour. From this needs to be taken£2.0 per hour of overheads. That leaves £9.43 per hour to pay the tailor a wage (minimum wage is £8.21 from April 2019), which is then taxed. If the various tasks accidentally take longer, insurance is more expensive, or fabric costs more, etc. then the pay left for the tailor goes down.

So while £150 for a coat looks like a lot for one item from a whole outfit for a hobby carried out on 5 or 6 weekends a year, there are not many variables here. The cost of fabric cannot change, the cost of insurance, website, etc cannot change, so a cheaper coat can only mean less money to pay for the non-productive time, the time taken to make the item or to pay the tailor.

Such has always been the nature of business but I hope that you now have a better idea of what is involved in that costly (not expensive) item of costume you want to purchase compared to the High Street fashion you bought last week.