The Importance of Breeches

/The Importance of Breeches

If we were Tudor re-enactors as a family, then breeches would have been very important to us; the shape and flamboyance of them being a key question for any outfit. We are not and so, for many years, they were not. Somehow, “soldiers” don’t have fancy breeches.

Thirty years ago, when my husband first took up this strange hobby of re-fighting parts of the English Civil War on odd weekends of the year, breeches were not the first thing that I made for him, but they were the second. I put a lot of time and effort into the doublet but the breeches were described as “short trousers made of wool”. Those first ones had straight legs, a modern fly shape and a pull cord tie at the waist and leg cuffs. However, under the Soldier’s Coat they looked enough of the part and lasted many years.

Slowly over the coming years, we started to see people with differently shaped breeches (do I go around looking at men’s breeches?). Unconfined versions with flapping leg ends and fringes of cord; very baggy and voluminous ones that looked almost Tudor; very tightly fitted ones. Also over that time we had been buying various pamphlets and booklets on the clothes of the Civil War and how to make them. So, with two growing boys making breeches became one of the mainstays of the family hobby.

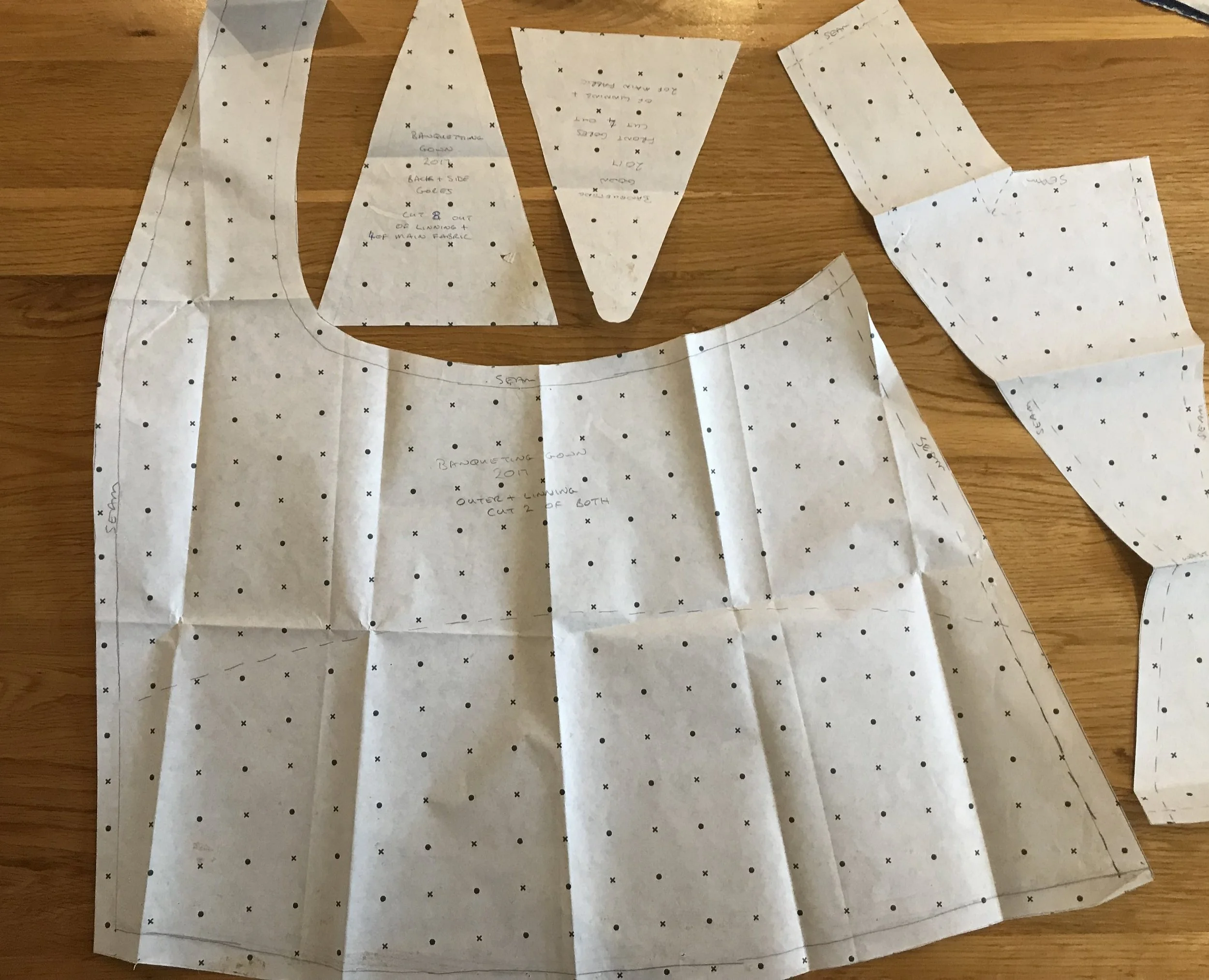

When I decided this year to start making costume for sale rather than for family and friends, it was time to up my game. Time to improve my most recent patterns with some of the newly researched information that has been coming out recently. I was fortunate enough to get two orders for breeches at about the same time that my husband bought the “Modern Maker” series of books by Matthew Gnagy. These books do two things - they provide a system of re-sizing patterns to any height/girth based on a tailors’ technique described in the 16th century and they give patterns from original tailors’ manuals from the 16th and 17th centuries. I decided that the 1640 pattern was the one to use - narrower than earlier patterns but still gathered around the waist.

Breeches Pattern on Lining Fabric

A Buttonhole Panel

One aspect of all of the patterns given by Matthew’s books is a lack of any fly or closure arrangements. For Tudor hose and breeches, that is because a cod piece is laced into the front, so there is no need for any overlap or fly. By the time we get to the Civil War, cod pieces have been out of date for decades. So I needed to find a method of fastening these breeches.

For many years I had been unhappy with the “designed in” fly overlap, especially with lined breeches. There is always a point where the fabric of the crotch has to start crossing over and it often leaves an odd change of direction.

So I was very pleased to find that another book I have, The Seventeenth Century Men’s Dress Patterns from the School of Historical Dress, had a solution. They only have one extant pair of breeches - a puffed pair of trunk hose. These had originally been laced across the front - possibly even with a cod piece - but they had been modified to have a buttonhole patch inserted into the seam on one side. The patch was finished of around the edge with grosgrain ribbon.

The buttonhole patch was a revelation to me and I now believe it would have been used commonly by tailors in the “production line” system that they had for some parts of clothing. In the modern sense, I was able to manipulate the small patch easily when either hand or machine stitching the buttonholes. I ruined one and only wasted two small rectangles of good cloth and one of the stiffening fabric, the replacements cut out of the waste “cabbage” left over from the main cutting. I was able to work on the buttonholes separately from the breeches.

In an historical sense, I can imagine an apprentice being given the patches in bulk and told to practice buttonholes. Totally ruined ones waste very little fabric all cut from scrap anyway. Poor but serviceable ones could be used for low value clothing, e.g. soldier’s uniforms. Once the apprentice gets better they can work on the patches while other people are cutting and stitching the main garment, bringing them together at the last minute so making fabrication quicker and more sure.

Breeches with buttonhole patch hidden in front folds

So for me, I will not go back to including the buttonholes in one side of the main breeches fabric unless I have to. I hope you find this information useful and strongly recommend both of the book series that I have mentioned. They are excellent sources of historically accurate details such as this.